I’m sorry I didn’t do a post for April. It’s totally my own fault: I forgot it was May. What even is time? Never could get the hang of Thursdays. By the time people poked me about it, it felt a bit late, and I thought I’d do a combo post for both months together. However, April was a very exciting and busy month, because I got a first vaccine shot, and also I was helping long distance with Ada Palmer’s class papal election, and then May was… well, the snow melted, and as from last Friday we no longer have a curfew, and I may get a second dose of vaccine this week, and all shall be well and all manner of things shall be well.

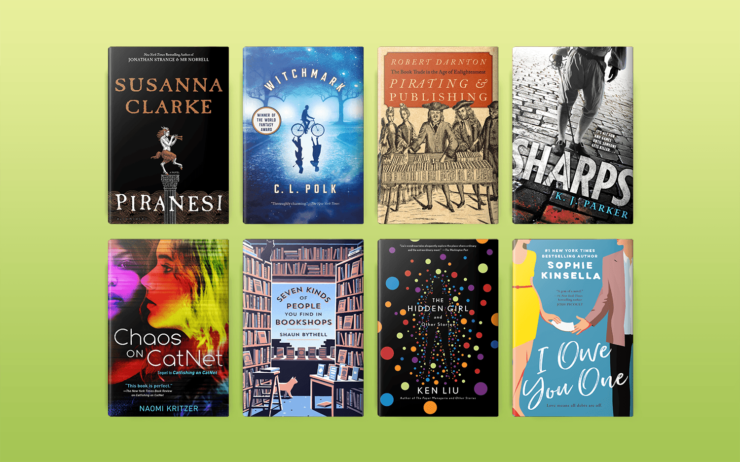

In April and May combined I read a total of 32 books, and some of them were unexpectedly wonderful.

Storm Tide, Marge Piercy and Ira Wood (1998)

Re-read. I read this book when it came out, but I don’t think I’ve read it since, so I’d forgotten all the big things and only remembered the details. This is a story about a town on a sandbar in the ocean and a man who was a baseball success until he was a baseball failure and an older woman who is a lawyer and various political and romantic shenanigans. There’s a character, the “other woman”, who makes me really uncomfortable and whose level of reality doesn’t quite seem to work, and there’s a “somebody dies, oh who dies” teaser opening that is annoying. So it isn’t as good as Piercy’s standalone novels, but then again I don’t know it by heart either, so that’s a plus.

Four Gardens, Margery Sharp (1935)

Clearly observed novel of a woman’s life seen through four gardens—England, class, being a different class from your family, and growing up. I enjoyed reading it, and read it pretty much non-stop.

Sylvia Townsend Warner: A Biography, Claire Harman (1989)

Bath book. Following on from Townsend Warner’s letters to Maxwell and a book of her short fiction, a biography that doesn’t have an ebook. It’s really good though, a very interesting look at her life and work and personality, full of detail and illumination.

The Undomestic Goddess, Sophie Kinsella (2005)

Hilarious gentle novel about a woman who messes up at her job and goes to work as a housekeeper by mistake, with love, vindication, and a huge amount of sheer readability. Whatever it is that makes me keep reading the next sentence, Kinsella has lots of it. Also she’s really good at being funny from situations arising from characters.

Cold Magic, Kate Elliott (2010)

First in a very interesting fantasy series, a kind of alternate history fantasy where we start in Britain in a world where the Romans didn’t decisively win, there’s no Christianity, there’s lots of magic, and now there are starting to be (of course) airships. The point of view character is a girl with a mysterious background that turns out to be much more mysterious than she could have imagined. Elliott is always a good storyteller, but she’s not much for concision—this is a long book, and I read all of the preceding books while I was reading it. There are two sequels and I own them and want to read them, but I’m not often in the mood these days to spend as long as this immersed in one story.

A Thousand Days in Venice, Marlena di Blasi (2002)

A memoir by a food writer about meeting her Venetian husband and falling in love and moving to Venice, honest, open, fascinating. It’s full of wonderful description, and not just external but real internal description of the times it didn’t work as well as the times it did. This is a perfect example of what books like this should be like. I’m not very excited by the recipes, though I have made a couple of them. But after reading this I really care about Chou and Fernando. Highly recommended to anyone who wants to read about Italy.

You Had Me at Bonjour, Jennifer Bohnet (2014)

Sadly, this was not a good book, even for a romance novel set in—it was set in France, in fact, but that wasn’t what was wrong with it. It chugged along slowly and exactly as expected, with nothing standing out about it at all. It wasn’t even amusingly bad. Thoroughly mediocre.

Witchmark, C.L. Polk (2018)

Literally the only thing my mother taught me was not to judge a book by its cover but do I listen? I do not. I was late to the party on this book because of the offputting cover which led me to believe that cycling would be sufficiently central to the book that I wouldn’t enjoy it—some cycling enthusiasts are so overwhelmingly evangelical about cycling that it can become uncomfortable for disabled people, and the cover, and only the cover, made me think this might be like that. Fortunately, however, I read a short story by Polk that was so brilliant I put aside my prejudice and got hold of it and read it and it’s great and now I’m kicking myself. Also the cycling isn’t a huge thing at all. Amazing world. Amazing magic system. Wonderful narrator. Just all round a marvellous read. The only good thing about my procrastination is that both sequels were out by the time I got to the end, and so I didn’t have to wait. This is a well-thought-through world at a mostly WWI tech level with lots of magical secrets and connections to other worlds and it’s doing very interesting things with the emotional analogues of history.

Out of Istanbul, Bernard Ollivier (2000)

This is an amazing, wonderful travel book that I highly recommend to everyone who even slightly enjoys reading travel memoirs. Ollivier is a French journalist who retired, and his wife died, and he was in his early sixties and his sons were grown up and he didn’t know what to do so he walked to Santiago de Compostela, which is a thing people do. And when he came home he wanted to go on another long walk so he decided to walk the Silk Road from Istanbul to China, and while he was doing it meet people and think about mercantile history and not military or religious history, and go through many countries. But he decided to do it in stages, one chunk every summer, and then go home and write about it in the winter, and this is the book of the first summer, when he walks out of Istanbul. He’s an excellent companion: French, never afraid to laugh at himself, and the twenty years between when he did this, starting in 1999, only makes it better. Also, when he got home he started a foundation in France to have juvenile offenders go on 2000 km walks instead of to prison, which costs less and has far better results. More countries should do this. Highly recommended.

The Stone of Chastity, Margery Sharp (1940)

An anthropologist decides to investigate a folkloric item in an English village, taking along his widowed sister-in-law and nephew, and causing havoc. It sounds ridiculous, and it is ridiculous actually, but also delightful. Sharp is very good at evoking character, and she’s funny, and sometimes that’s enough.

The Summer of the Great-Grandmother, Madeleine L’Engle (1974)

A memoir of the summer in which L’Engle’s mother had dementia and was dying in L’Engle’s summer home, with family all around her, braided with L’Engle’s memories of her own childhood and her mother’s stories of her history and the family’s history. There’s an odd reserve in this somewhere, even as L’Engle is baring her soul it feels as if she’s keeping a lot back. Also, as in the earlier volume of her memoirs, I hate her husband, he’s a jerk and he says mean things and she isn’t aware of it. I’d had enough of L’Engle by the end of this book and will save the other two volumes for later.

I Owe You One, Sophie Kinsella (2019)

It occurs to me that Kinsella’s novels are about financial independence and career happiness just as much as they are about romantic happiness, which makes them chick lit rather than romance. This one is about a woman and her family business and drawing boundaries between herself and her family—and between the things she’s always wanted and the things she actually wants. There’s also a very nice romance going on, which is again about transactions and boundaries. Kinsella is great.

On Wings of Song, Thomas M. Disch (1979)

Re-read, book club. I’ve written about this before, and I said “it’s as if Dostoyevsky and Douglas Adams collaborated on the Great American Novel” and I think that sums it up pretty well. It’s that rare thing, a book that’s like a mainstream novel, a book about what shaped a person, but in a very science fictional world where what shaped the person is very science fictional. But there’s no fantasy of political agency here. It was a very divisive book for book club; some people loved it and some hated it. I was a little worried it would be too depressing to read now, but not a bit, I raced through it.

Rescue Me, Sarra Manning (2021)

This is a romance novel about two people and a rescue dog, and as usual in Manning they are people with psychological issues which she does well. Nevertheless, this book lacked some of the spark of her earlier books, or maybe it was just me. Maybe it was because it did the thing where it alternates POVs between the couple, which often makes everything too obvious. It was fine and I’m not the slightest bit sorry I read it, but if you want to try Manning, start with Unsticky.

The Hidden Girl and Other Stories, Ken Liu (2020)

Another Ken Liu short story collection, hurrah! This is not quite such an explosion of virtuosity as The Paper Menagerie but it’s also excellent and has some of my very favourite Liu stories. He just keeps getting better and better—but there’s a lot of stories here about VR and people living in computers, which gives it less variation than his earlier collection. Terrific.

Stormsong, C.L. Polk (2020)

Second of the Kingston books, and from the point of view of Grace, sister of Miles who is the POV character of the first book. Because she is more politically compromised, and more caught up in her society, I liked her less. The story also suffers a little from being a middle book—we are aware of the world, and it isn’t climactic. This is mainly dealing with ripples from the revelations of the first book. But it’s very well done. Looking forward to the conclusion.

Chaos on Catnet, Naomi Kritzer (2021)

Sequel to Catfishing on Catnet and very good. If you liked the first book grab this as fast as you can. I went through this almost without pausing. If you haven’t yet read the first book, then grab that one first, because this inevitably has spoilers. It’s YA, but don’t let that put you off at all, the genre is speculative resistance, or hopepunk. Terrific book.

Seven Kinds of People You Find in Bookshops, Shaun Bythell (2020)

There’s nothing less funny than a joke that doesn’t work, and sadly this one doesn’t. A bookseller attempts to classify customers in an amusing way that isn’t amusing. I’ve worked in bookshops and I had Bythell recommended to me, but this struck me as very feeble.

The Innocent and the Guilty, Sylvia Townsend Warner (1971)

Bath book. A collection of Warner short stories—uncomfortable, unforgettable, powerful, and often having the effect of a thunderbolt, even though they are so seemingly small in scale. She’s amazing. I have no idea how she did what she did. That’s so great.

A Thousand Days in Tuscany, Marlena di Blasi (2004)

Second book by di Blasi about living in Italy, this one even better than the first, with the same deep sincerity and openness and closer relationships with friends. This is a book about making friends, making a life, uprooting and rerouting, and also eating and drinking. Wonderful treat of a book.

Beneath the Visiting Moon, Romilly Cavan (1940)

Another Furrowed Middlebrow reprint of an almost forgotten woman writer. This is an odd book about a blended family in that class of English people whose lives were about to be so utterly upended by the war that they wouldn’t exist anymore. The coming war hangs over the book like a breaking wave, partly consciously (it was published in 1940, and set in the summer of 1939) and partly unconsciously, because Cavan didn’t know what was coming after the time when she was writing it and still imagined a war like WWI. In any case, it is the story of Sarah who is just about to be eighteen and can’t bear her life and can’t find any other way to live, about the crush she has on an older man, about her mother’s remarriage to a widower with children, and about the claustrophobia that is life in that class and time. It’s very well written, and very well observed, but suffocating.

Virtue Politics: Soulcraft and Statecraft in Renaissance Italy, James Hankins (2020)

Very long, very brilliant, deep dive into intellectual history of the concept of republicanism and legitimate government in the Renaissance; incisive, fascinating, original. They really believed—until Machiavelli pointed out that it didn’t work—that education could make people into better, more virtuous, people, who would govern better because of this, and that it was their responsibility, as tutors and educators, to do this.

Walking to Samarkand, Bernard Ollivier (2001)

Volume two of Ollivier’s trip on foot on the Silk Road, in which he goes on from the very spot where he collapsed at the end of the last book and walks all the way to Samarkand, sometimes happy, sometimes sad, talking to everyone he can talk to in whatever language they have in common, constantly remarking on the scenery, the Silk Road, the kindness of strangers. There’s a lot about Iran in this book, at a moment (2000) when anything could have happened. Just as good as the first volume.

The True Heart, Sylvia Townsend Warner (1929)

Bath book. So in 1929 Warner decided to write a version of the story of Cupid and Psyche and set it in the Norfolk Marshes in the 1880s, because why wouldn’t you? Vivid, distinct, full of images that stand out and unexpected moments, and not like anything else in the world. Warner is one of the best writers of the twentieth century, they should teach her in lit courses, there’s so much there and it’s so vibrant and resonant.

Sharps, K.J. Parker (2012)

Aha, finally another full length Parker than I like as much as Sixteen Ways to Defend a Walled City! Thank you whoever recommended this one, it was great. It also gave me a perfect example of plural agency, just too late for the Uncanny essay on plural agency but so it goes. This is the story of a group of people made into a national fencing team and sent to another country for mysterious and complex reasons—to provoke another war? To settle the peace? Five men and a woman, different ages, who know different things and have different agendas, set off on this fencing tour and everything goes pear-shaped. This may be in the same medieval/Renaissance fantasy world as some of his other books, but it doesn’t matter whether it is or not, this is entirely a standalone and really terrific.

Under the Italian Sun, Sue Moorcroft (2021)

Romance novel set in Italy, pretty good too, though with unnecessarily convoluted backstory.

Pirating and Publishing: The Book Trade in the Age of Enlightenment, Robert Darnton (2021)

A new Darnton! I was so excited. This one is a kind of companion to A Literary Tour de France; it looks at the details of how publishing worked and how pirate publishers outside France produced books that were illegal but available everywhere, and when I say “how” I mean specifically how. Fascinating.

Life’s a Beach, Portia MacIntosh (2021)

This barely qualifies as a romance novel set in Italy, as it’s mostly set in Britain and on a private island that doesn’t actually exist but is technically in Italy. However, I don’t care because this was delightful. The odd thing about it is that it came very close to being embarrassment comedy on more than one occasion and then just skated right on by. When I stop and analyse it, it’s all really silly and does rely on embarrassment comedy and big misunderstandings, but while reading it I didn’t care because the voice was so good and I liked the characters and believed in them and their absurd situations. The protagonist’s first person voice was sufficient to make this pop and sparkle. Will read more MacIntosh.

The Assassins of Thasalon, Lois McMaster Bujold (2021)

New Penric and Desdemona novel—all the other installments in this series have been novellas. This was fun, and I enjoyed it. Don’t start here. Well, I suppose you could, but… no. Start with Penric’s Demon.

The Vanishing, edited by Shae Spreafico (2017)

This is a poetry collection that starts with a poem of 99 words and goes on through a vast range of poems from the whole planet (some in translation) that are each one word shorter, until at last there’s a poem with one word and then one with none. This may sound like a gimmick—all right, it is a gimmick—but this was a terrific collection of unexpected juxtapositions and I loved it to bits.

The Best of Nancy Kress, Nancy Kress (2015)

I really do think Nancy Kress’s best work is all at short form, and I think that at short form she’s one of our very best writers. There’s not a dud in this collection, and all of them are thought provoking and different from each other and just great. “The Price of Oranges” reduced me to tears even though I’ve read it several times before.

Piranesi, Susanna Clarke (2020)

I bought this as soon as it came out but I hadn’t read it yet because I was afraid it would be depressing, but in fact it was not only wonderful and amazing, which I’d expected, but surprisingly cheerful and close to a comfort read. I read it all in one day without stopping, and I recommend it unreservedly to everyone. It isn’t a book in which no bad things happen, but it is a book where everything is very satisfying, and there’s an infinite house full of statues and the sea, and you’d love this book, you, if you’re reading this, it’s almost certain you’d love it and it would make your life better.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published two collections of Tor.com pieces, three poetry collections, a short story collection and fifteen novels, including the Hugo- and Nebula-winning Among Others. Her novel Lent was published by Tor in May 2019, and her most recent novel, Or What You Will, was released in July 2020. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here irregularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal. She plans to live to be 99 and write a book every year.

So glad you’re back! I was afraid you might have decided to end this series.

I’ve been reading a lot of Margery Sharp via Furrowed Middlebrow, though I read completely different books. (I read The Stone of Chastity long ago via a nice old (as in original American publication I think) copy I found in an antique store.) So I read her first novel (Rhodedendron Pie) and the novel from right before The Stone of Chastity, Harlequin House. Both delightful, Harlequin House especially. And just the other day I finished her unusual collection of three novellas set in the 19th Century, Three Companion Pieces, decidedly different from her usual work. (My review is here: Three Companion Pieces.) (This is a book not (yet) republished by Furrowed Middlebrow, and I wouldn’t be surprised if Scott doesn’t choose to use it — there’s a lot of outstanding Sharp novels left, after all!)

And I’m very intrigued by Romilly Cavan. I will get to her soon.

I read the wrong Sylvia Townsend Warner book I think, Mr. Fortune’s Maggot, which was fine but didn’t thrill me. I’ll have to find some others.

I have a copy of Sharps but it’s one of the K. J. Parker books I haven’t read yet. Glad to hear it stands with his best.

I am only now reading (that is, listening to) my first Kate Elliott novel, her latest, Ascendant Sun. (I’ve read and enjoyed a lot of her short fiction.) Ascendant Sun is tremendous fun so far, pure Space Opera, as you suggest, not concise, and also perhaps a bit too ready to echo character cliches of that genre, and also a fair amount of fortunate coincidence. But exciting as heck.

And as for Piranesi, it’s a masterwork. Clarke is a remarkable writer. As you, say, it’s a surprisingly undepressing book for a book in which, really, some very bad people have done some very bad things — but within that context there are wonders, triumphs, and much beauty.

I’ve been looking for this post. I’m so glad you’re back. Thanks as always for your suggestions –I will have to try Margery Sharp, and I’ve added other titles to my list. However, I have to disagree with you about Sophie Kinsella. Based on an earlier recommendation of yours, I had read the two you mention here and they made me drop her. I’m no stickler for much realism in romance novels, but despite promising premises, these just got ridiculous.

You aren’t the only one for whom time doesn’t exist. I hadn’t realized you weren’t here.

Yay for more Darnton- such interesting subjects.

I wholeheartedly agree with Catnet!

Like you, I’ve been waiting on Piranesi. Glad to hear it’s comfortable.

So many great recommendations in this list. I always appreciate your honesty; it helps immensely to know when not to bother.

I’ve only read The Best of Nancy Kress from this list. Her short stories were my reintroduction to Science Fiction after the typical reading of Phililp K Dick, Atwood and Butler in my twenties. Perhaps that’s not typical. Kress disabused me of my prejudices and my shockingly simplistic idea that Science Fiction is just space wars and action sequences. I believed that even with the contrary evidence from Atwood and Butler. I don’t know why we readers create these limiting belief. I wasted a lot of good reading time.

My favorite from The Best of Nancy Kress is Laws of Survival. I will always have a soft spot in my heart for her. She opened the door into this world and now I feel truly rich.

I believe there are 11 or 12 books I will read from this list. Thank you.

Piranesi! I read it last fall and LOVED it. I’ve been recommending it to anyone who will listen, so I’m glad to see it favorably reviewed on your list!

I was missing your April list last month but it was worth the wait to see you’ve discovered the Ollivier books! I love these both so much and am eagerly waiting for my library to get the third (already on order so the wait shouldn’t be long).

Claire — I think it was your recommendation that brought them to my attention. I’m half way through the third one now, and it’s just as good.

Hi Jo, I’ve never commented before but your KJ Parker love begged a response from a die-hard fan: I taught K. J. Parker’s “The Hammer” in an Engineering Ethics at university a couple years ago and it was a huge hit. Probably my favorite by Parker, and I can’t wait to hear if you like it too!

Welcome back, Jo! I’m another who missed you last month.

Thanks for sharing your thoughts. It may be time for me to read my copy of Witchmark.

Thank you as always for your wonderful suggestions — I look forward to them. Completely agree on Warner – Lolly Willowes and Kingdoms of the Elfin are two of my favorite books and I’m been reading The Corner that Held Them (as I’m on a Middle Ages kick) and it is just as witty and delightful as her other books.

Piranesi was my favorite read of 2020 and a mesmerizing book. I will definitely check out Furrowed Middlebrow to discover more writers.